- Home

- Peter Moore

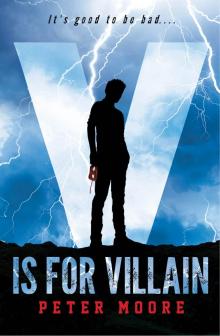

V Is for Villain Page 2

V Is for Villain Read online

Page 2

It was good to know that he was thinking of me when he had such major things to deal with himself. But every time he called, I was left thinking, This never would have happened to him. I mean, obviously. It couldn’t happen to him. With his strength and speed? If there were any way for him to get hurt like this, he never would have been taken into the Justice Force to replace Dad as Artillery.

Even though I wasn’t supposed to, I kept touching the big scar on the back of my neck. It wasn’t too sore, but it was new and I couldn’t keep myself from feeling it, kind of like how it was hard to keep your tongue from going after that loose tooth when you were a little kid.

The doctor had told me that if the damage had been just a tiny bit more, if my neck had been forced another millimeter or two, I would have ended up a quadriplegic. So even though I was left with a whole lot of titanium just under my skin, I had to consider myself lucky.

Uncoded

My third night home, I woke up with my T-shirt soaked. Even though the sheets were cold from my sweat, the room was hot.

Ever since I woke up in the hospital, I had been thinking about what happened on the field, and more important, why. It was weird: I had heard that voice in my head, but it’d felt as if it had come from someone on my right side. I can’t wait to see this, it had said. This had been happening more and more, sometimes a couple of times a day. It was making me nervous.

It wasn’t all the time, and the truth was that I couldn’t correlate the incidences with any conditions or situations. The only factor that was common to all the times it happened was that the voices were usually emotional: either highly angry, deeply sad, or even ecstatic. In other words, high emotion. I didn’t recognize any of the voices and it happened mostly outside the house, a lot in the hallways at school.

At first, my thought was that I was developing aural powers, but I realized it couldn’t be that. The voices weren’t external noises that were just low volume or far away. But it didn’t feel exactly like I was hearing the sound. It was more like I was feeling the idea of the sound. That wasn’t how things worked for Audiates. But it was how things worked for people who were—to use the clinical terms—wacko crackers, around-the-bend loony tunes. And I was already enough of a smudge on my family’s reputation. The last thing they needed was for me to be insane, too.

I dug out the book, buried under a pile of old PT class T-shirts, from the bottom of my closet. It was an actual book, with paper pages. I didn’t want to risk leaving any trace on the Internet, either by computer searches or e-book downloads. The book was Psychopathology in the Undiagnosed Person by Dr. Miklos Kohane. According to Doc Kohane, auditory hallucinations were usually a symptom of a few heavy-duty psychological conditions, none of them good. I’d been having them for a couple of months by that point, and that worried me. I read the book some more. I was relieved to find that my not having “command hallucinations” (“Go kill the president!”) was a good sign that I wasn’t a serious danger to myself or others. Yet.

I read until I couldn’t take it anymore. If I wasn’t, in fact, crazy at that point, it was probably just a matter of time before I went off the deep end. There was no way to avoid it if it was in my genes.

If it was in my genes. That was something I could at least find out.

I took off my sweaty T-shirt and put on a fresh one. Then I went downstairs.

The bottom step creaked loudly. Mom called out from down the hall. “Brad? Is that you?”

Good. She was home. I called back, “Yep, it’s me. Where are you?”

“In the study.” I went to her office and took a seat in the chair in front of the desk.

Mom was sitting on the short couch, her legs tucked up under her.2 She had a reading lamp on and a copy of American Journal of Metahuman Genome Studies open, four or five more volumes on the floor next to the couch. There were dozens of Post-it notes sticking out of the journals.

Although she was a geneticist, not a psychiatrist, I needed some answers about the voices and I figured Mom might be able to help. I did what I could to sound casual. “Hey, remember that time I went to the lab with you and we looked at Blake’s DNA image?”

“When you were writing that paper for school.”

“Yeah. So, I was just wondering, did you ever run my DNA?”

“Well, yes. Soon after you were born.”

“Can you bring it up on your computer here?”

“Now? I could, but I would have to log in to the GenLab database, do a search to pull it up, and then tomorrow, I’d have to explain why I was accessing the server to read gene maps that aren’t among the ones we’re studying. Why?”

“I was just thinking that I’d like to see it.”

She closed the journal she was holding. I noticed, though, that she kept a finger tucked in, to mark her place.

“Honey, looking at your DNA won’t change anything. All it’s going to do is make you feel worse. It won’t give you powers you don’t have.”

Huh. Okay, so she thought this was about my being upset that I wasn’t powered, a known sore point at home. I would use that. It was a lot better to let her think I was concerned about not having powers rather than concerned about losing my mind. I could let her think what she wanted and still find out what I needed to know.

“What would my DNA look like under the analysis program?”

“Genes for enhanced powers are shown in bright colors. You would have an indigo one, for your intelligence. But other than that, it would look essentially like a Regular’s DNA.”

“And any diseases that a person is wired to have—those show up in the genome map?”

“Like what?” she asked.

Oh, just stop asking these questions. There’s no point. A voice again.

“What about mental illness? Does that show up?”

“Of course.”

“How does that look?”

“Depends on what the illness is.”

“Let’s say, I don’t know, schizophrenia.”

“Like any other nonpowered gene. It’s coded in white and carries a number.”

“And that kind of marker would be there from birth, right?”

“Well, from before birth, yes. From just after fertilization, when the blastomere is forming. Why would you ask about mental illness genes?”

Better back off on that. If I asked whether she had seen that on my DNA, I was going to pull the conversation in a direction that would be hard to redirect. “No real reason. I’m just trying to get a full picture of how all this works.”

“Why?”

“Just wondering about it, I guess.”

There was a longer silence than I liked, but she took a breath and broke it. “You know I completely understand how it feels, not having powers…or not having the powers you want.”

It was time to get out of the conversation. “I get that. But it’s still uncomfortable to talk about.”

She took in a breath. “Well, I’ve been thinking. If you believe it’ll help, we can discuss getting you myo-augmentation.”

“What?”

“It’s true that I don’t usually approve of cosmetic enhancement, but if you would feel better about yourself by having a mesomorphic muscular body, I could look into getting you a consultation.”

An instant bodybuilder physique was not about to change me in the way I really needed. “Thanks, but I don’t think that’ll make any difference.”

“Well, give it some thought. If you decide it’s something you want…” Mom said. I started to wonder if maybe it was something she wanted me to get. I would fit in with the family image a whole lot better with great big biceps, pecs, and delts. But without true power behind it, it would all be just a facade.

“I’ll keep it in mind,” I said. Yeah, that was a good place to keep it. In my mind, wher

e all the voices were. Right in the middle of the crazy.

Battle Broadcast

On my first day back in school, ten minutes into third period, there was an announcement over the PA. It was our principal, the Colonel, as he still liked to be called, years after his retirement from the Quad Squad. “Pardon the interruption. We have just learned that members of the Justice Force have located and engaged the Gorgon Corps in battle. Teachers, please turn on your monitors and tune in to channel 221. Students, watch this carefully. It’s likely to be a truly historic event.”

Miss Connelly switched the channel on the monitor at the front of the room and turned off the lights. The camera work was very shaky. Whoever was shooting the battle was doing it using a long telephoto lens. Obviously, it wouldn’t be a great idea to be too close to the action, unless your desire to document the event was greater than your desire to remain alive.

The image had that green glow of a night-vision camera, which meant the battle had to be happening somewhere in mountainous terrain on the other side of the earth—Asia, maybe, or the Middle East.

It was a pretty good fight, probably the best I’d seen in months. There were flares shooting through the darkness on the screen, which could have been mistaken for artillery, but were actually firebombs hurled at the Justice Force by Inferno. With the darkness, the distance, and the angle, it was hard to make out much detail, but you could see Phaeton3 bodies falling on the battlefield. There was a blur of red, gold, and blue.

“Hey, Baron! Wasn’t that your brother right there?” Dean DeStefano shouted.

“Looks like him,” I said. A hand-to-hand fight had begun, and it was hard to tell who was winning.4 The only way to see the guys from the Gorgon Corps was from the glints of light reflected off their dark uniforms. Of course, everyone in the Justice Force could be seen, even in the darkness. They wore bright uniforms exactly for this reason.

The view switched to another shot, closer and from an angle that looked like it was being taken by someone lying on the ground. There was a crawl on the bottom of the screen that read, LIVE! JUSTICE FORCE (USA) ROUTS GORGON CORPS AT CHITWAN VALLEY IN NEPAL. FIVE MEMBERS OF GC CONFIRMED KIA, INCLUDING LEADER TOXICON, WITH NO CASUALTIES TO JUSTICE FORCE.

My classmates burst into applause and cheers. Even Miss Connelly clapped her hands. I joined in with everybody else.

On the screen, I could see the silhouette of my brother kicking ass and taking names.

And all around the classroom, I could feel eyes stealing glances at me. No doubt, several kids had to be thinking, How can one brother be such a star hero and the other one be such a complete nothing?

And truth be told, I was wondering the same thing myself.

Blur

At lunch on that first day back in school, I sat in the cafeteria with Virginia, Shameka, and Travis at our usual table. Shameka wasn’t talking much, because her voice modulator had to be repaired. It was giving off a buzzing tone when she spoke, and occasionally squealed with reverb. If she spoke without it, she wouldn’t be able to control her amplitude and could make a whole lot of people go deaf. She didn’t have to worry about getting on a hero team; she already had a written offer from the Supersonics, and she had preregistered her hero name—Deci Belle.

The girls and I were watching Travis eat. It was amazing; you’d think he had the power of Matter Ingestion. Though there were obvious benefits to MI, like being able to eat fire and then become blazing hot, or to eat acid and then spit caustic lye, there probably weren’t a lot of useful powers to get from eating crazy amounts of pasta salad.

I couldn’t eat. I was too angry. “Can you believe that they didn’t do anything to Rick Randall after what he did to me? I mean, not even a single day of detention.”

Virginia and Shameka looked at each other, then at me. Obviously they were thinking, Bad topic.

“I mean, seriously,” I said. “The kid broke my neck, almost crippled me, and now I’ve got half a hardware store implanted in my spine, all because he wanted to show off. And the school does nothing to punish him. Nothing at all. I mean, doesn’t that make you sick?”

Shameka suddenly became very interested in the texture of the croissant still on her plate. Virginia was looking at me, and I could see it on her face: Boy, I really don’t want to talk about this with him now.

“Hello?” I said. “No opinions at all? You’re fine with the fact that they did nothing?”

Virginia took on a casual tone of voice. “Well, actually, he was given fifty points for a good sack. ‘Perfect form’ was what Mr. M had said. That kind of put Randall in the top position for accrued PT valor points.”

Valor? “Whoa, whoa. Wait a minute. Rick Randall damn near kills a guy in PT class, the most blatant example of unnecessary roughness possible, and he gets rewarded with extra points and the top honor position?”

“Well, that pretty much hits it on the head,” Virginia said, trying to sound lighthearted.

Wow. I wasn’t sure which was more disturbing: that the school did nothing to discipline a violent scumbag just because he’s got the so-called hero thing happening, or that my supposed friends didn’t even care.

My Own Worst Enemy

The events of seventh period didn’t do much to increase my sense of belonging. Even though I was wearing the same navy uniform as everyone else in the class, I wasn’t like them. Not looking the way most of them did—that is, being a whole lot smaller than the average guy in the hero track—wasn’t the worst part. Lots of people had powers that weren’t obvious from looking at them. For me, though, physically speaking, it was more or less what you see is what you get.

I’m pretty sure I wasn’t the only one who ever zoned out in class, and it wasn’t as if I’d been sending death beams from my eyes to the teacher. But for some reason, Mr. Q decided it was time to make an example of me.

“Hello, there, Brad! Mr. Baron? I do hope I’m not boring you with this lesson.”

“Huh?” I said, sitting up in my chair and blinking. Most of the kids had too much honor to turn around and watch another student get disciplined. They faced forward or turned their gazes away. Except for the few who wanted to see me get verbally throttled.

The left corner of Mr. Q’s mouth curled upward. “Certainly, it isn’t as if the fate of civilization will absolutely depend on your knowing this material.”

“Well, no. Probably not,” I said.

“But it is possible. Wouldn’t you agree it’s possible?” Mr. Q was expecting me to admit I was wrong and apologize for arguing, and then pay rapt attention for the rest of the period. Which, I admit, I should have done.

“The thing is, Mr. Q, I really don’t get why we all need to take aeronautics when not all of us can fly.”

Mr. Q nodded his big head a few times. “Ah. I understand now. So what you’re saying is, you don’t see the value in your classmates learning principles of flight because you feel it doesn’t benefit you, due to your own abilities. Or lack thereof.”

I knew that Mr. Q had a reputation for being a great teacher, but I thought he was an arrogant, elitist bastard.

I was of no interest to him. He only really paid attention to the high fliers.

“You know, that’s not a bad idea,” he went on. “Let’s change the curriculum. We’ll get rid of any classes Brad Baron doesn’t like. We’ll only keep the ones that he’s good at. It’ll make for a pretty short school day, won’t it?” He grinned, looking for laughter from his favorites, the few toadies who were all too happy to oblige.

Still, I felt like I had a legitimate argument. “I totally understand how anyone who’s able to fly would find this really useful. But I don’t see how it’ll make any difference in life for the rest of us.”

Virginia turned back toward me and glared. I knew her well enough to read from her face exactly what she was thinking: He�

��s going to blast you any second. Stop being an idiot! And, of course, she was right.

And that might have been the end of the issue, but Mr. Q felt the need to discuss it some more. “You don’t see how the study of aeronautics would make any difference to you,” he said. “So pursuit of excellence is not something that matters to you. Is that it? And we shouldn’t study powers that you don’t have. Which doesn’t leave much to study. But I suppose not everyone can live up to the legacy of your father. Or your brother.”

So there it was. I’d figured he was headed in that direction. Your brother is such a hero; your brother was so wonderful when I taught him; your brother stepped up when tragedy befell your poor father; your brother is an idol for kids and adults around the world…blah, blah, blah. And then the inevitable—spoken or unspoken: So what went wrong with you?

I was tempted to point out that Mr. Q himself didn’t exactly compare to Blake or my dad, either, so he might not want to go down that road. But I kept my mouth shut.

“So, Brad,” Mr. Q said in his most reasonable voice, “whatever shortcomings you may have, you don’t think knowledge of aeronautics would be helpful to you if you’re, say, fighting someone who is able to fly? Let’s say you’re up against a Phaeton. Now—”

“It’s pretty unlikely that I would ever find myself up against a real Phaeton,” I said. I wasn’t trying to be a smart-ass, but I was aware that I was sounding like one.

“Fine, then. Say you’re fighting—oh, wait. Why fight anyway, right? Maybe you think it would be better to debate an enemy into submission instead.”

“Well, there. That would be great, wouldn’t it?”

Because of the injuries he’d sustained in the Battle of Des Moines, the left side of Mr. Q’s face was made of FerroAlloy. And when he got mad, it would lose shape, going liquid metal. I could feel the floor vibrating a tiny bit and the room getting warmer. All signs that he was losing his temper.

Damn His Blood

Damn His Blood Red Moon Rising

Red Moon Rising V Is for Villain

V Is for Villain